Review | Relooted - 'You Are Not Thieves'

Relooted hooked me on premise alone. “A puzzle platformer where you case museums and—” I’m in. What/who are we robbing? “—steal and repatriate African Art objects.” Incredible. I am easily sold on robbing a bank (in a video game), and for far less nobler motivations than literally returning stolen artifacts back to the spaces where they would be the most culturally appreciated. This is the kind of fantasy video games were meant to recreate. It’s a game that appeals to my particularities and areas of study.

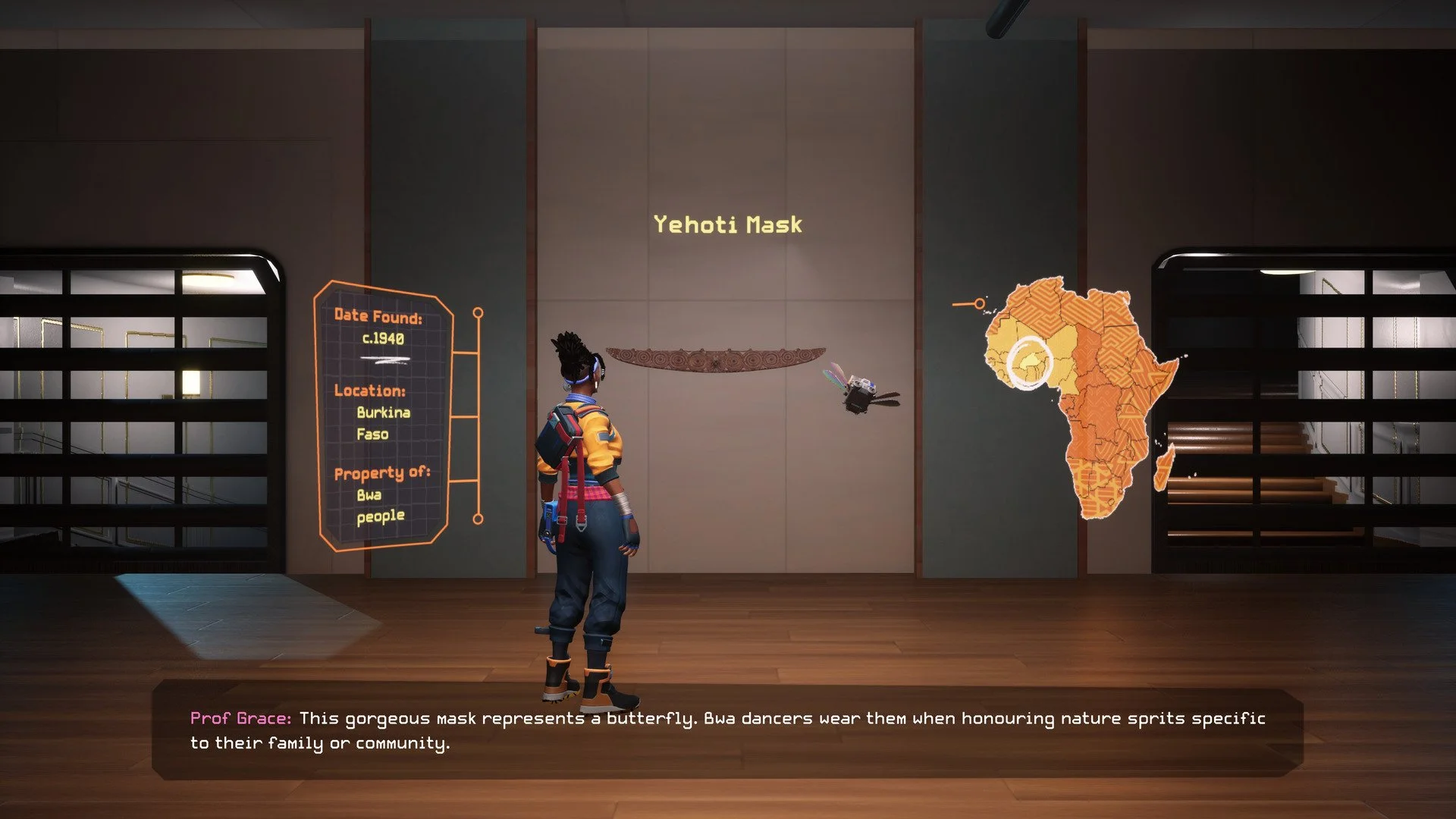

I’m no expert, but I did get an Art History minor where I primarily focused on African Art, specifically on religious, artistic, and cultural productions of the African diaspora in Latin America. So I will say with absolute certainty the best part of Relooted is the amount of care that was given to the presentation of these art objects. So much passion went into placing them in their proper cultural and historical contexts, so the game ends up being one of the most informative and useful sources of knowledge on the basics of African Art in video game history.

I do have some nitpicks, primarily regarding some slight pacing and narrative issues, a little bit of hand-holding, and some setpieces that felt very artificial because they didn’t elicit much in the way of emotional payoff. But do not let me be misunderstood: flaws and all, Relooted should be required playing for anybody who at least has a passing interest in African Art, or, frankly, anybody who wants to start thinking about culture and art outside of the commonplace Western canon.

Welcome to the secret hideout, let me introduce the crew: Nomali’s your playable protagonist, the action woman, the runner, the one who does all the fancy stealing and parkouring; Fred’s our man-in-the-chair; Trevor’s the locksmith and safecracker; the silent guy over there is Ndedi, an acrobatic infiltrator; we also got Cryptic, our hacker; and Luso, the muscle. Supporting from the background are Professor Grace and her mentee Etienne — both of their brains contain treasure troves of valuable information on the various African artifacts you will be recovering.

Outside of the intermissions between levels, where you walk around the town or talk to your crewmates, you could divide the game into three phases. Just like any good heist, the plans are segmented into various steps:

1) First, we case the joint. Look for entrances and exits, plan the routes and strategies. How do we get past those security cameras? Can our hacker take care of those robots? Are we gonna block ourselves in because of a shutter-door closing when the alarms sound?

2) Then, we get our escape ready. Make sure our route is clear, so we can grab the African Art objects and—

3) Run!! The alarm has been tripped, drones are on their way! Reach the getaway van before time runs out and we’ve made it out with some cultural artifacts to be returned to their home countries.

The first phase primarily sees you controlling your own little drone to get a feel for the layout and get the brain juices flowing as to what obstacles and puzzles will await you. The latter phases are the real meat and potatoes of the whole affair: they will see you engaging with never-too-complicated platforming puzzles and then running as fast as you can, using your parkour skills to the fullest by jumping through obstacles, sliding through low openings, and making daring leaps.

While I enjoyed the characters, who are all incredibly likeable and varied, Relooted does have an incredibly uneven pace. The first half of the game saw me gathering up members of the team slowly and steadily, bombarded by tutorials and VR training that killed any momentum. I want to repatriate African Art objects, please let me engage with the artifacts directly. Please, Fred…not another VR mission in those drab cybernetic environments, levels that serve as mere tutorials and lack the vibrant colors and imaginative sets of the rest of the game.

Additionally, despite the squad’s heroic and noble intentions, none of the heists felt like they had much weight to them. There didn’t seem much at stake for most of the narrative, no personal or interesting motivations outside of the (admittedly) already incredible proposition of returning African Art objects.

The game also has a bad tendency to hold your hand, which feels mechanically dissonant. I am being trusted with valuable information on African Art — with the understanding that I can engage with these objects critically, place them in their proper contexts, and study them under the correct ethical leanings — but the game does not trust me enough to figure out the gameplay by myself. If I am at my first or second heist, I can understand the need for a character to remind me that a table can hold a shutter open, but, if I’ve already done that a dozen times, I do not need Trevor to once again repeat, “You can probably use that table to block the shutter gates from closing!” ...Yes! I know!

Part of me wants to brush these off as minor criticisms, because the game did allow me to turn many of these difficulty and accessibility settings off, and I could also turn off the path-making that literally tells you how to complete the escape phase of a level. But, there’s an argument to be made that even in the “Normal” difficulty, the constant barks of dialogue reminding me about gameplay elements I’ve already engaged in were excessive, that many other games have similar modularities with their difficulty and accessibility yet do not incessantly annoy the player.Even with the yellow highlights and objective indicators turned off, Relooted does not pose much of a challenge on the gameplay front, neither in its puzzle sections or its parkouring sections, which many times left me feeling deflated rather than elated from pulling off the heist of the century.

The game shines when you are actually dealing with the African Art objects. They are rendered in such spectacular detail, and the game prioritises imparting the cultural information as to why these particular artworks deserve to be repatriated.

My colleague Wallace Truesdale said it best in his review:

“Not once is the violence of these artifacts’ displacement shied away from, nor is the illegal nature of Nomali and her family’s nighttime activities. It’s a clever choice that makes their mission a clear matter of justice—a challenge to anyone who believes all laws, the very ones that allowed these stolen cultural works to be on indefinite ‘loan’ and hidden away when repatriation parties come knocking, are moral and must be obeyed despite their authors’ intent and actions. The mission of the Afrika Appropriations Association (the best of several names Trevor gives the team) asks players to consider what constitutes a crime, as well as who are the real criminals.”

As someone with a decent knowledge of African Art, I was impressed by the way the philosophy of the game supports the ethos under which African Art should be studied. One example of this ethos is how Professor Grace explains why we shouldn’t be using the term “slaves”. (You say “enslaved person” or “person who was enslaved”, because nobody is born or wants to be a “slave”. Africans were forced under torturous and brutal systems of slavery by European colonial powers, so we acknowledge their humanity and personhood first and foremost)

Relooted is a breath of fresh air because it actively combats the tired cultural narrative that turns Africa, a vast continent rich with varied and complex cultures, into a monolith. The Yoruba, the Igbo, the Kingdom of Benin — all are vastly different cultures with vastly different artistic and religious productions. What many colonisers saw as “backwards” rites and rituals were actually complex systems of spiritual and philosophical thought and action.

And, yeah, the game lacks a certain biting scholarly or academic complexity, which is totally fine; I have faith that the folks at Nyamakop intended to ease people into knowing and understanding African Art without the heavy weight of academia potentially breaking down player interest. What I want to propose is that people keep studying and learning about African Art outside of Relooted, and hopefully more people will uncover a valuable trove of cultural knowledge, different ways of seeing and thinking about the world.

The game is explicitly asking people to engage with the debate of repatriation, which is complex and difficult, as are all things worth discussing. I urge people to explore repatriation efforts and ask themselves the difficult questions, like Kwame Antony Appiah, who poses the query: Whose Culture Is It, Anyway?

Relooted does the work of all great Afrofuturism: It asks us to dream of utopias while respecting and acknowledging the past, engaging with it with the gravitas and complexity it deserves. If we lived in a fair world, a better world, a kinder world, we would’ve already had a thousand games like Relooted, and maybe one of them would’ve adhered more closely to my stylistic and mechanical desires. As it stands, Relooted is worth playing on premise and intention alone, and in a media landscape that struggles to show African-ness in the light it deserves, it has more than earned its flowers, and my respect and admiration.

Relooted was played on PC with a code provided by the publisher.