David Cole Craves Ownership | Winter Spectacular 2025

The transience of this digital world exploits you. We are fodder in an endless churning of consumption that has silently conquered us. We write off participation in this — our gear cranking away in an impossibly large machine — as “survival”. The world is hard and therefore we need our Netflix. We need our Spotify. We need our Nintendo. I am guilty of this. It often rings of the oft-quoted expression “You will own nothing and you will be happy.”

But consider how these things we invest so much of our time into are ephemeral. They exist on a server somewhere, not in our homes. We are not paying for works, we are paying for access to works. We scroll mindlessly down the terms and conditions that detail the many ways we are agreeing to the temporary nature of that access. We inevitably accept, because acceptance is the final barrier to entry. And we push away any lingering thoughts of what it is we have accepted so that we may enjoy six hours of a well-edited documentary. Or another episode of our favorite adult-oriented cartoon. Or The Game Awards nominee Troy Baker as Harrison Ford as Indiana Jones.

In 2024, a story made the rounds about Valve stating to users via its customer support that “your Steam account cannot be transferred via a will.” That statement, out of context, doesn’t seem to mean a lot. The average person probably thinks “just write down your password” or “don’t tell the corporation that you’ve died.” Both reasonable enough courses of action, to be sure. I recently had a conversation with an old buddy about this story and their response was “I can’t take it with me, so who cares.” Can’t take it with me, of course, being a charming colloquialism for the fact that all possessions are ephemeral as life itself is ephemeral. One day we will die and our Steam library isn’t going with us, wherever it is we go.

I thought about this for a while, not wanting to argue the finer points of consumerism with a friend. Later that day, I was going over my collection of physical video games that has grown, to be blunt, out of control. According to the app I use to track said collection (perhaps an indictment of my behaviour all on its own), I have in my possession just over 900 video games. This is not counting any digital libraries or periods of time, be they the indie XBLA games I rooted around for in 2009 or the long-gone Wii Shop® Virtual Console™ titles saved to an SD card almost two decades ago. And, to be clear, it does not include Steam. Rather, this is a collection of plastic boxes, molded cartridges, and optical discs that take up the real estate of two considerable shelves within my modest home.

Marie Kondo would innocently look to the camera and smile, knowing that she had quite a lot of work to do with me.

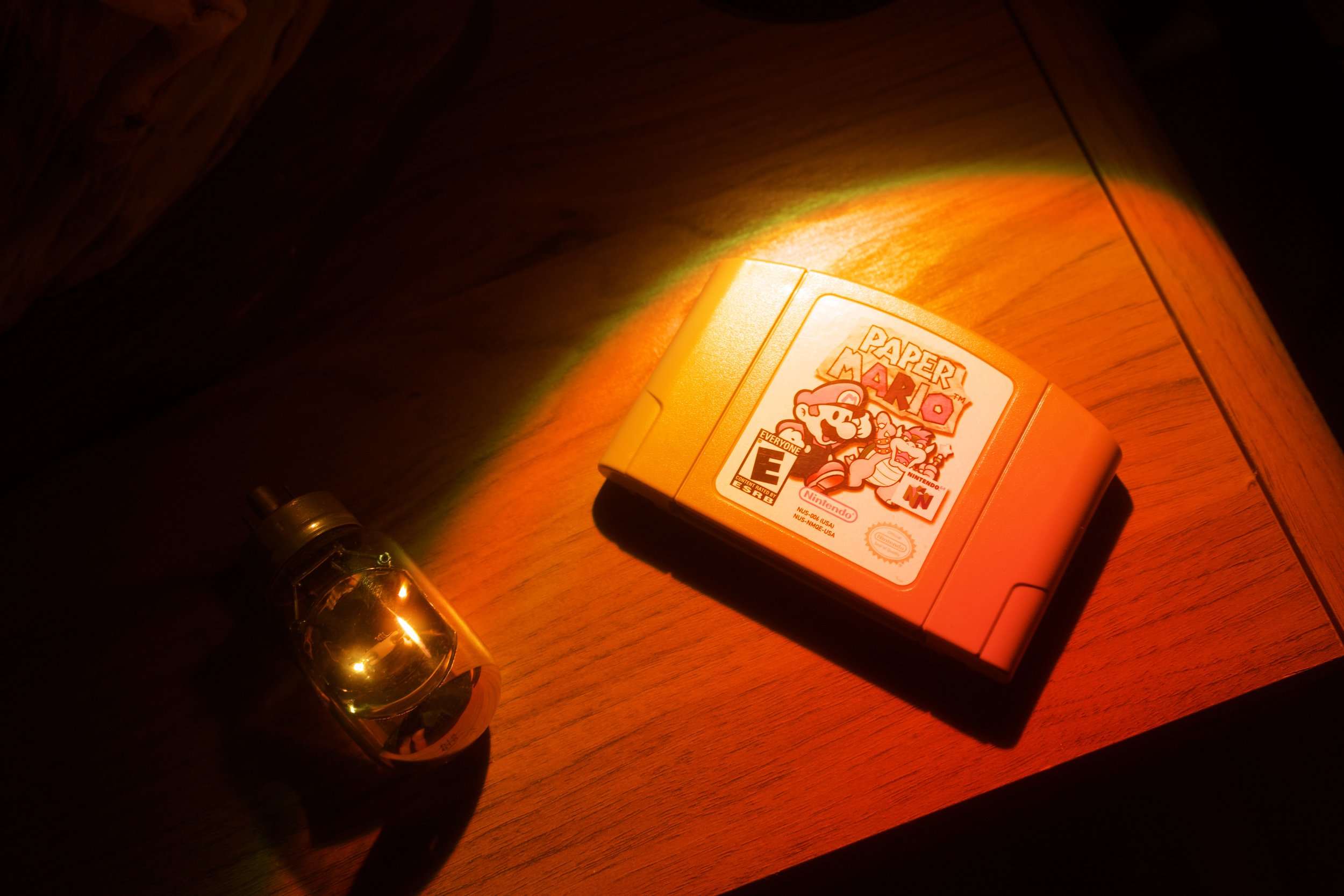

But as I was looking at these two shelves, all lacquered in the unfortunately college-chic pure black paint I’d settled on long ago, my eyes fell on a video game entitled Paper Mario. This year marked its 25th anniversary. I held the shell of gray plastic in my hands, looked at the largely yellow cover sticker depicting everyone’s favourite plumber and the auspicious visage of the king of all koopas, and remembered a brisk morning twenty-five years prior. I stood outside a KB Toys in the city of Lexington, Kentucky, then the largest place I thought could possibly exist, and anxiously stared inside the shopfront window at the many other children bustling about this paradise of playthings as if it were a normal day. I remembered the large train set that hummed along near the window and the three boys who were so enamoured by it that they didn’t notice the sickly child staring at them. I remember my Nana, then still spry and smiling, urging me to go inside and promising I could pick out any one thing to enjoy at home once a dreaded surgery I was to soon undergo was behind all of us. I remember the anxiety of choice, remarkable in a six-year-old. And I remember settling on the familiar face of one Mario Mario, nervously reaching for a star amongst a cavalcade of colorful characters. Something about that look on his face, a combination of determination and consternation conveyed in simple lines, brought a feeling of comfort to me. If Mario was nervous then it was okay for me to be nervous.

This was the one.

And now, twenty-five years later, I held a relic of that moment in my hands. I had seen it all once again as if it had just happened; the smell of that morning air, the envy I felt toward those boys, the encouragement and love an old woman showed me when everything seemed so impossibly scary. Here it was, cradled in the same fingers that had so readily accepted it over two decades ago. I took it to a console, I plugged it in, and I played a little bit.

This is the game which first challenged my reading ability and comprehension. A story told almost entirely via dialogue bubbles will do that. Below the poverty line in Appalachia, this itself was a gift I could not have recognised at the time. An interest in words spiraled quickly into a need to string them together myself. Soon, pages of poorly-constructed ramblings and observations (something I am still accused of from time to time) flowed out of my youthful hands like water down a clear mountain stream. Without Paper Mario — no, without this copy of Paper Mario, I would not be the man I am today. Someone peddling words despite all signs pointing to the unfortunate truth that they are an exceptionally difficult thing to peddle in the year of our Lord 2025.

I’m going to go out on a limb and assert that the licence to a video game will never inspire the same kind of reflection or self-orientation that I experienced while turning over Paper Mario in my hands.

We do not value the things that shape us. We consume so much content that it can become difficult to even know what it is that actually is shaping us anymore. Was it the Oscar-winning film or the TikTok my niece forced me to watch that morning, or the one after it, or the one after that one? We spend so much of our time consuming that we don’t give ourselves time to digest. We don’t allow ourselves to reflect, to consider, to learn. We are merely existing in a stream of movement from one thing to another thing, like salmon surrendering to instinct and swimming upstream to lay eggs and die.

Every game I have taken note of this year has invariably been met with sentiments of “Cool now do X!” or “When is the next Y?” and so on. A Pokémon midquel is greeted with questions as to the status of the next “proper” installment. A new battle pass within Fortnite brings the impossible demand for what will make it onto the next one. Even a remake of Dragon Quest that, frankly not enough of you are talking about, prompted community discussion of when Dragon Quest 8 or 9 would see the same treatment. In part, it’s the very human desire and pleasure of speculation. But it’s also a symptom of a much larger and more sinister issue.

We consume more than we create. We become the salmon and head into an endless stream of content, yet we somehow find ourselves collectively demanding more. To meet those demands, budgets balloon and schedules crunch. Human labour is reduced to statistics, which can easily be examined and replicated by machinery. We continue wanting and wanting, crumbs of half-eaten works tumbling down our potbellies as we reach for the next thing and the next after that.

And because of this lack of digestion, this wading ever upward into the oncoming stream, we have become forgetful. We are so single-minded about trends and the zeitgeist that we don’t take a blessed moment to think why we enjoyed something. Sometimes we are so addled in our pursuit of more and more that we turn to others to formulate our opinions for us. The influencer, the streamer, the critic. We devour and regurgitate their thoughts, believing that we are either in agreement or (as is the case with many of my viewers) disagreement, and that is that.

It’s arguable that today’s largely-digital landscape has devalued the objet d’art, or at the very least demanded of us a reconsideration of what it is that constitutes the art. Not the method of delivery, but the content and the content alone. Content that the controllers of delivery systems — be they Valve or Microsoft or Nintendo or whatever impossibly big corporate entity — can revoke from us at any time, for virtually any reason. A rampant permission we have blindly granted virtually every time we’ve quickly scrolled down a list of terms and greedily clicked on a highlighted button reading “I Accept”. Events sometimes outside of our control, be they getting banned from an online ecosystem or death, render our invested time, money, and emotion almost entirely moot.

We own nothing and yet we are so unhappy.

Of course, it should be said that the desire to buck the inevitability of an all-digital future naturally locks one out of experiences. Some games are only available in digital formats. Some of them are incredible pieces of art: 1000xRESIST, Tactical Breach Wizards, Caves of Qud all are, at present, solely available via digital distribution. Therefore abstinence, as usual, isn’t the answer. The answer is purposeful, considered, and controlled consumption. Too long have we glorified the purchase of the video game. Too long have we casually spoken about our backlogs. Too long have we said to the powers that be that the consumption of content is more important to us than the content itself.

I challenge you, dear reader, to reconsider your relationship with the video game in 2026. Consider where you might be in twenty-five years. No small task, but a worthwhile one. Consider that something you own, that meant something to you, may find its way into your aging hands once again. Or, should the worst come to pass, into the hands of someone you love. Think about what that would look like. Is it more satisfying in this hypothetical to see someone looking down at the worn plastic case housing a disc ready to be used? Or, would the preferable image be a piece of paper with a password scribbled down that may or may not lead to access of the same thing?

I, for one, think that the answer is obvious.

Header Image Credit: Cassie Payne