Mik Deitz Has Survived A Hard Game, Hard Year, Hard Life: Silksong, Celeste, and Sadomasochistic Joy

To be extremely blunt, albeit at the risk of sounding melodramatic, 2025 was one of the most difficult years of my twentysomething life, with extreme pain and suffering caused only in part by the release of Hollow Knight: Silksong. Hovering at 85% and nearly 60 hours played — something generally unthinkable for me, a girl who gets bored of and scared by the inflated runtimes of even the most basic RPGs — I beat the actual final boss of Silksong nearly two months after release, a big feat considering I had to be convinced to pick the game up at all. It wasn’t that I didn’t hotly anticipate Silksong, nor that I don’t love the unique brand of search-action fuckery that made the original Hollow Knight one of my most played games on the Switch. I simply wasn’t interested. I had too much going on in my life to give the title more than a passing glance.

When Silksong first broke containment at Gamescom, I was knee deep in orchestrating a move from one New York City neighborhood to another. Okay, so the apartments were only a mile and a half apart, but I still had to pack up all my physical and emotional baggage into a ridiculously large U-Haul and schlep it that distance without killing anyone, least of all myself. I was in the middle of a profound crash out, one that lasted for weeks on end, each day bloated with self-medicating to escape all of the parts of myself that bubbled to the surface throughout the year, thoughts and feelings and emotions that I was ashamed of and overwhelmed by. So it’s safe to say that when the spooky, difficult bug video game was getting buzz and Becoming Discourse, I was a little bit distracted.

After a few days, however, I noticed something pretty important. I was scrolling through bed one night, probably high or drunk or both, and it dawned on me that people would not shut up about how unfair and cruel Silksong was. The enemies did too much damage, the bosses were unreadable, Hornet’s moveset (especially her diagonal slash) called for too much precision, the biomes were designed by a sadist. Many essays and Bluesky threads were written about how Team Cherry, those goofy Australian freaks, didn’t understand they had made a game that cruelly punished the player for their mistakes. It hurt their feelings and spit in their face and said rude things about their mothers. And I am completely unashamed to admit that this is what finally piqued my interest.

I have a habit of turning toward difficult games during difficult times. Previously, I chose to complete Celeste while writing my Master’s dissertation. During the weeks I was bullshitting academic-sounding prose about The Last of Us Part II and amorality and ludonarrative hermeneutics (look it up, nerds, this piece is already too long without me explaining it), I was also scaling Celeste Mountain for the umpteenth time, attempting speedrun strats that I gleaned from GDQ runs and dangerously strangling my Switch in multiple countries trying to conquer the A, B, and C sides for every level. When I finally submitted the paper — which I did get a passing grade on, by the way, even if it had multiple spelling errors and accidental comments left in it because Microsoft Word is devil’s spawn — I had completed everything except for Farewell, the tough as nails free DLC that Maddy Thorson and company created to specifically fuck with me.

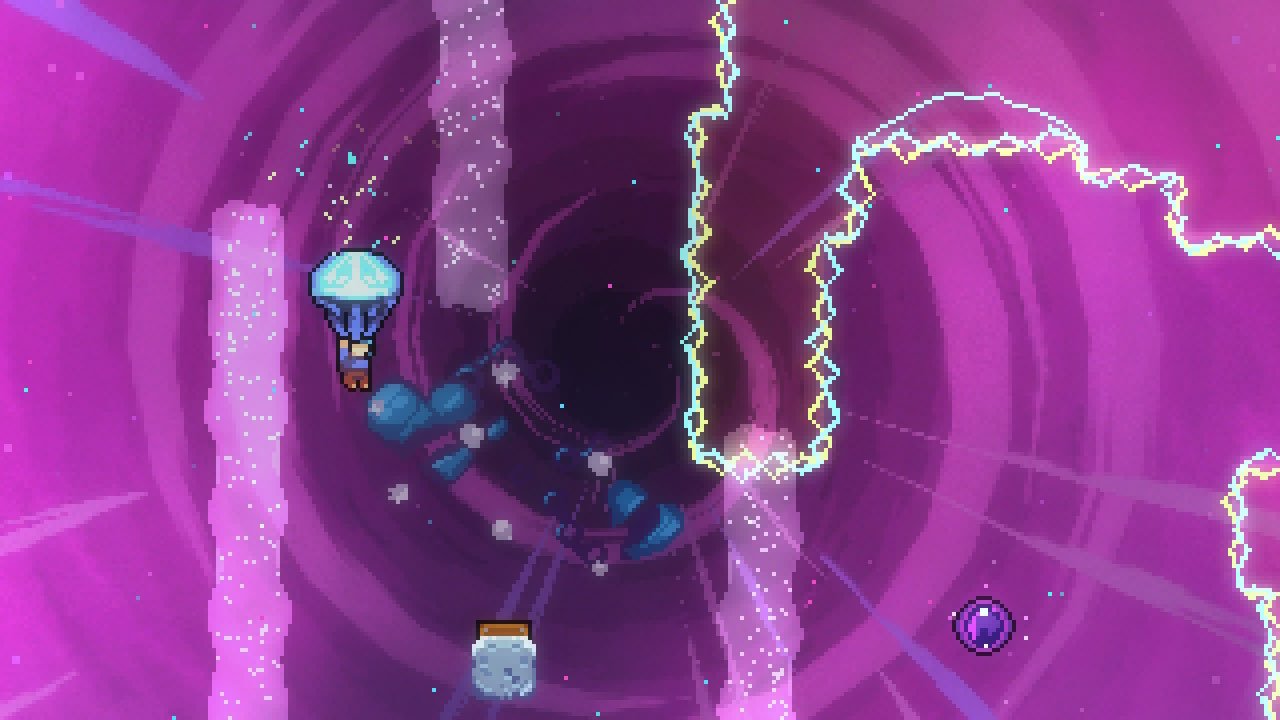

I had tried for years to beat the final screen, which is a stupidly precise, minutes-long maze of electric currents and flying jellyfish and jumps angled just so. If anyone wants to talk about cruel-but-doable game design, no one does it like Extremely Okay Games. When I finally flew through this electrified maze, replete with exploding fish and so many bottomless pits, in one graceful swoop and reached the end of the level, I almost let out a guttural scream on New Jersey Transit. I saw something near impossible and slammed headfirst into it again and again until I beat it. It felt better than finishing a 50,000 word paper I slaved for months over. It felt earned in a way that my professors and parents may be sad to hear.

In a small, completely-dislocated-from-reality way, playing an extremely hard game while suffering in my personal life felt like an acceptable form of self-harm. I couldn’t stop my dissertation from being a painful slog, but I could throw a poor red-headed girl at spikes and down bottomless pits for as long as it took to win. Victory, however small, was a sweet treat within my grasp. The pain of failure was only as vast as my skill ceiling and tolerance levels. I could push myself as hard as necessary to reach the end of a level, without ever actually physically or emotionally devastating my real-life body and mind. I lost my temper now and then — my imaginative cursing really deserves its own dictionary — but I was always a hair’s breadth away from success. I knew that it was only a matter of time until I won: I had the skills, I had the patience, I had the stubbornness. Reality was more slippery, a slimy, amorphous blob of intolerable emotions and unhealthy coping mechanisms. I couldn’t grasp it without falling down a pit of despair, sinking beneath layers and layers of fuckedupness that needed extreme therapy and a pharmacy’s worth of medication to unravel.

It’s probable that Silksong would’ve captured me if it released at any random point throughout the year, but as I was settling into my new apartment, my desires laying at the bottom of a bottle, my lungs happily set ablaze with disposable pens and CBD cigarettes, I latched onto it like a tick. To be clear, now that I have authority as Someone Who Has Beaten Silksong, it absolutely is a sadistic game made for sickos and freaks. Contact damage being two masks is an objectively bullshit design choice. Enemies taking, at minimum, four to five hits even in the opening areas is horrible balancing. And, despite some people getting super behind it, the diagonal pogo is difficult to perfect and asks a bit too much of the player to be the default moveset. But that was the point for me: I am one such sicko freak that Team Cherry designed the game for, and I wanted Silksong to kick my ass again and again and again until I was finally able to kick it back.

I relished any and all opportunities to do difficult things in Silksong. Like Madeline before her, I threw Hornet into unwinnable situations repeatedly until I stole victory from the mandibles of defeat. I summited the frozen wastes of Mount Fay with panache, fully taking in the indulgent animation and art design throughout a dozen or more deaths, and many, many falls to a lower level. I gleefully explored Hunter’s Marsh, the first early-game hellscape that required the diagonal strike for platforming, and killed hundreds of ants like a can of Raid. For every boss that took hours of (im)patience and trial and error — the Last Judge, Cogwork Dancers, the goddamn Savage Beast Fly, and Groal the Great you piece of shit, I will kill you and your entire leaf-peeping family — I sat down, hit my pen, and listened not to Christopher Larkin’s wonderful score and evocative sound effects, but to punk music, sad girl rock, anything that loudly assaulted my eardrums enough to ground me in the Here and Now. I wanted to wreck Pharloom’s culty ass. I tried and tried and tried again, unwilling to give up, a dedication that I simply couldn’t give myself in my personal life. As I fell further apart, Pharloom became safer, more peaceful, more free.

If I was the religious type, I could go long about how Pharloom’s overall design harkens to the Catholic ideas of penance through pain and paying yourself out of sin through indulgences. Other writers have already done that. Instead I can talk about how, in a small way, cleaning out Pharloom was penance for the way I treated myself. How, on a day when I didn’t eat much, I could still find an ingredient for the gluttonous Great Gourmand to chow on. How, if I drank a few small beers and felt glued to my bed, I could still wander various biomes searching for a way forward, out, through. How, if I was finding ways to hurt myself in real life, I could forgo blood and bruises by trying Skarrsinger Karmelita a few dozen more times. How, for my inability to get myself out of the ever-deepening gutter, I could slowly bring peace (and black goop and danger and eventually more peace) to a land filled with hopeless, stupid little bugs.

Like Hornet, I never gave up on the bugs of Pharloom. I could save (some of) them; I could make Pharloom a place where actual kindness and care aren’t ground to dust through trials and tribulations created by and for a select few. The real people, like Sherma and Garmond and Zaza and every single fluffy little flea, who somehow found joy and community among all the suffering. Who saw a road carved from the bodies of dead bugs and — stupidly, courageously — walked it anyway. Even if I gave up on myself, even if I couldn’t stand the sight of another day dawning, there was always somebug who needed me. And I had a duty to help them.

Slowly, and often unwillingly, I was able to turn Madeline and Hornet’s sense of stubborn grace toward myself. It turns out that I play Silksong better sober. Shocking, I know. And a renewed sense of mindfulness and patience allowed me to defeat even the most frustrating of Act 3 bosses. In real life, I’m grateful to say that I’m on the path toward wellness, toward self-care and self-love and whatever other self-directed shit one needs to be a functioning human being. It isn’t an easy process, and it isn’t pretty. There are times that I feel trapped in a chrysalis, broken down only to my goopy essentials. I feel formless and aimless and raw, uncertain of when everything will be over, when everything will be better, when I won’t have to hide my emotions behind pixels anymore. I’m being forced to face all of my fears and flaws rather than run away from them, and I’m rebuilding myself into someone stronger, better, kinder, more real, but it’s gross and painful and violent.

The worst part of it all, I have to do it without the safety of a cocoon: I am becoming a person-shaped thing in front of everyone’s eyes. I have an audience for each struggle, each failed and successful attempt, each glorious, bloody, beautiful moment of becoming. There’s comfort in that too. As much as my brain would like to convince me otherwise, I am not going through this alone. I have my family, my friends, my stupid cats to support me, check in on me, cheer me on. If I fail — and I will fail often — if I don’t want to get out of bed in the morning, skip a run, feel the siren call of substances, spiral due to some ridiculous emotional situation, I don’t die or explode into a mess of silk or coloured circles: I simply get to try again later.

As this endless year ends and rolls into one that I can only pray will be better — not just for myself, but for all my trans sisters and brothers; for those being bombed and those being starved by militaries funded by my tax dollars; for those who are losing homes to an angry earth; for anyone who ran into the borders of themselves and found nothing but brick walls — Silksong and Celeste ring true as hopeful pleas. The world may be hard. The mountains that we climb may be tall, the paths that we travel may be exhausting, the world uncaring and cruel. But everything that we face is, in some small way, surmountable. Tomorrow will arrive whether we want it to or not, and with it, another chance to live life in a way that we choose. That I choose. It just takes a little grit, that’s all. Nothing good ever comes easy, does it?