Andrea Shearon's Game of the Year - Norco | Winter Spectacular 2022

This year, I felt crushed by games media. Not in the typical “oh well, here’s to next year” way, either. It’s more like a gaping maw of depression — a “something is on its way to gobble me up, but there’s little to do in avoiding it” sort of feeling of dread. I spent a lot of the year trying to make sense of a beast that places so little value on ‘content’ but wants an intravenous feed of said content 24/7. I’ve lost count of how many layoffs I’ve seen this year, but I think I could connect some lines between that, executive pay, and my acid reflux.

That’s a lot to explain my end-of-the-year perspective. I think this industry is slowly wringing my soul from me, but I’m still here. I’m lucky in that I’ve encountered so many incredible and talented people through my journey, many of whom showed me kindness while battling their own demons. I’m also, somehow, just as fascinated by the medium as ever, and I’ve got a tremendous amount of respect for the people making games. My relationship with this mess is pretty complicated, and only getting messier.

In a year where that felt more suffocating than usual, I hardly played a damn thing that launched in 2023, and as a result, I mostly stuck to older comfort games. As I look back, neglecting newer releases didn’t do much for my bad feelings about being here, oftentimes reporting on newer games; go figure.

But among the handful of new games I played this year, there was Norco. I say I played it, but going through this game was more an exercise in confronting yet another place eager to eat me alive while desperately holding onto the good that anchors me to it. So, I can’t deliver a lovingly curated list of ten games I would personally recommend from 2022. I can, however, tell you why I’m perfectly content with my one indulgent experience in choosing Norco during my free time. I can tell you what it’s like to intensely love a place this miserable, along with a little plea that you try this southern gothic point-and-click if you haven’t yet.

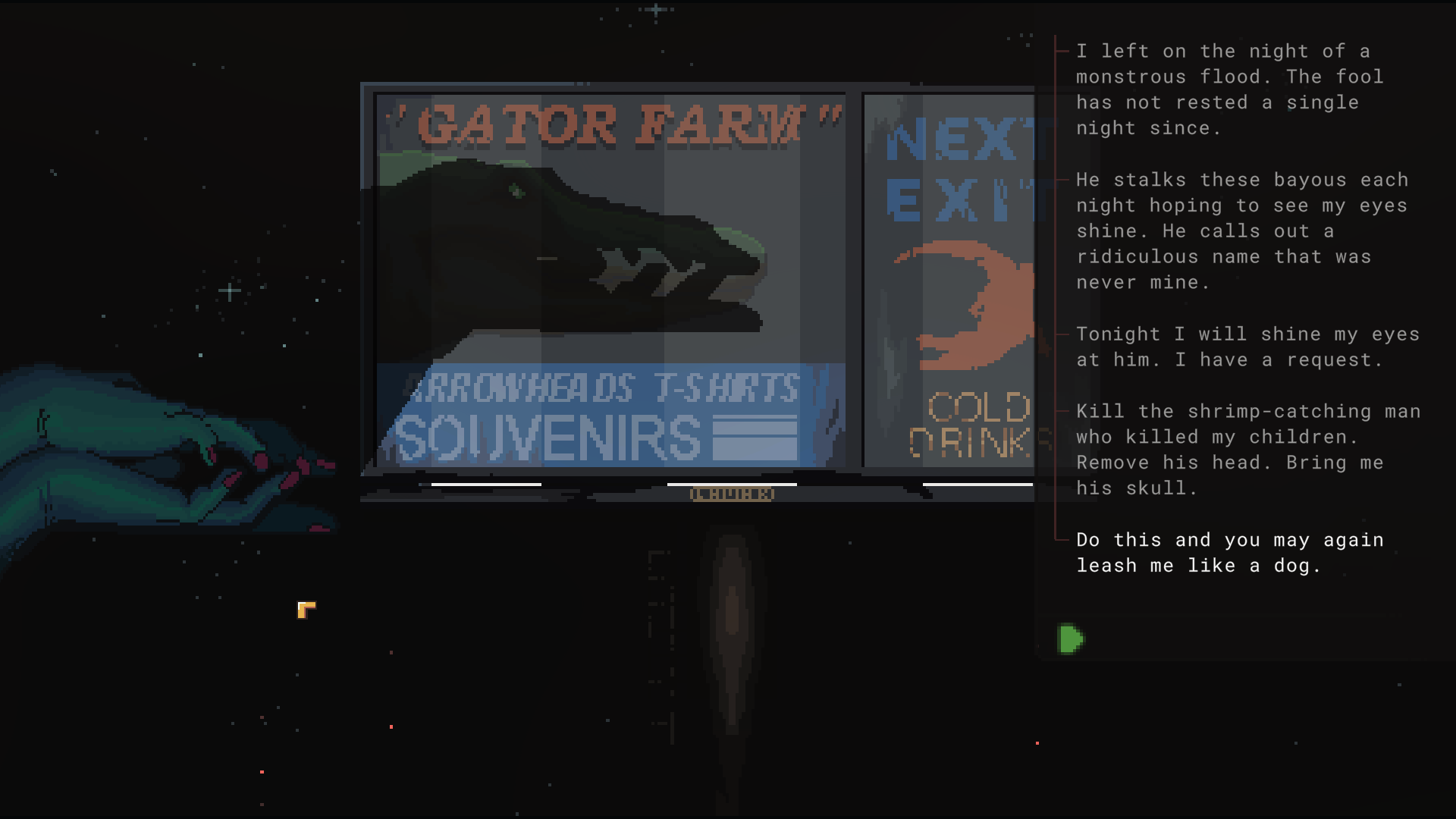

Norco’s distinct interpretations of a sci-fi Louisana are so nostalgic you can smell the earth and rust.

Into the Bayous

Norco, the game, is based on a very real city in Louisiana, not even an hour out from New Orleans. It shares the actual location’s namesake and plenty of little details that make it feel distinctly coastal, southern U.S. The creator, Yutsi, once told me stories about growing up there in an interview about the game. After playing, I could’ve guessed that even without the conversation. Norco, the game, truly loves Norco, the city.

Like many southern coastal cities, a massive industrial facility operates out of Norco. Those plants employ and practically run surrounding areas. The flow of life always feels vaguely familiar. Everyone knows somebody who works there or has a story about it; a distinct smell comes to mind, too. You go (or at least pretend to go) to church on Sundays and roll up spare change to buy groceries from a gas station. Neighbors either have a deep southern drawl or speak “Cajun” — I don’t know how to describe that other than broken French-English.

I’m from Mississippi; most of my family resides there and in Louisiana. Some live tucked away down roads that don’t exist in any official capacity — off-the-beaten-path detours hidden behind thick kudzu, southern pines, and sweetgum trees. I grew up bouncing between those places and impoverished southern suburbs closer to the Gulf of Mexico. It’s a place where the people feel just as oppressive as the humidity.

I’m never quite sure what anyone means when they speak of “southern hospitality,” but this fictional Norco has none of it. In its vision of a southern future — where poor folks live alongside the bi-pedal robots replacing them — the cast feels just as bitter as the people I left behind in my hometown. They’re easy to hate and hard to empathize with, and when you’re young and queer, a way out never seems to come fast enough.

The devil is in the details, Norco’s small nods to rituals and southernisms that are often painfully familiar.

It’s For The People, Not The Place

That’s what Norco’s lead, Kay, does. She runs. She leaves behind her mother, Catherine, whose love did not stop her from being a horrible parent, and a brother, Blake, who crumbles in the wake of Kay’s absence. The narrative picks up just as Kay returns to Norco after Catherine passes away from cancer and Blake goes missing. The reasons for his disappearance and the circumstances around Catherine’s final days grow murkier as Kay arrives in the Louisana swamps.

There’s a looming big bad in Norco, simply known as Superduck. It’s a sentient AI running hellish phone apps where it employs folks à la Uber and Doordash. Shield, the petrochemical plant ruling over the city, also has a clear interest in whatever the hell this superintelligence is. As the player, those pieces are the obvious driving force behind Norco’s torture. However, to the citizens entrenched in it, a shared enemy isn’t entirely apparent as they trudge through the days.

In those moments, when you’re meeting manifestations of rot and anger, Norco reveals how it makes the beast. People begging for a dollar in the French Quarter, those sitting in tents under overpasses, and the angry men screaming for any god that’ll listen are all symptoms of the city’s decay. Its residents are fuel for a machine keeping them destitute, profiting off of their bodies (and, quite literally, their minds) in an endless cycle of cruelty. Some characters lash out through violence against Kay, while others take a swing at their sci-fi overlords ruling from an omnipotent petrochemical plant.

If you’ve ever seen passing images of New Orleans, chances are they’re something from its iconic French Quarter.

Regardless of how grim that all sounds, Norco isn’t asking you to make knee-jerk judgments about the people you meet. Instead, it’s a grisly appeal to simply sit with them and know their circumstances. Norco lays out the worst it’s got to offer as if the city's spirit is proud of all its corpses — the sobbing of a father who lost his son to an online cult, the wasting moments of failed parent eaten by cancer, and the violence driven by capitalism.

None of its victims do much to endear themselves to you, but that’s not the point. There’s a prayer tucked away somewhere that onlookers understand how these people have become so averse to anything but their suffering, how they’ve fractured instead of unified against Shield or Superduck.

I’m Homesick – It’s Complicated

When you come from these places, there’s some strange comfort in visiting through Norco’s aberrant guided tour. There’s a moment when the narrative walks you through, organ by organ, how Catherine’s cancer ravaged her body. There’s a breakdown of the medical bills, Superduck’s inhumane payment plans, and her spiraling obsessions at the end. Shortly after, she recalls her failures as a mother through the exhaustion of it all. None of that is of any solace to her children, but it’s a window into how they come to love and resent both her and the city.

Growing up queer and poor in the south never makes declarations of love about home a clean and easy confession. I miss climbing through the ruins of an old chicken house and sinking into the knee-deep mud of a crawdad hole. I’m homesick for folktales and running barefoot down dirt roads. And along the way, I met elders and kids like me — people never given kinder terms to describe themselves with but still very much a part of the south. People who made these places beautiful, but still no easier to love.

Poignant vignettes that make you homesick for the decay.

The South is home to a lot of little places like that — a lot of people like Norco’s residents, some of them too far gone to save, and I’d never ask you to try. Yet, if you’re willing to take even just one thing away from Norco’s sobering perspective, I hope it’s an appreciation for how authentically southern this portrait of the future feels. There’s a part of the south so consumed by surviving that their resentment bleeds into every interaction, unable to find comradery in their shared suffering.

Norco is a nostalgic, complicated picture so familiar I can smell its bayous and taste its grief. And I reckon, even if you’re not like me and from the backwoods South, it’s still a transcendent narrative of apathy and endurance; a haunting tale that feels a little too analogous to today instead of tomorrow.

If you’ve only got time for one more game this year, please play Norco.

Andrea Shearon is a freelance writer with bylines at IGN, Fanbyte, USA Today, TheGamer, and more. She’ll try any game with a bit of romance and has a terrible habit of replaying the same old RPGs every year. Find her on Twitter, yelling about MMOs @Maajora, or tune into the monthly Materia Possessions podcast.