Review | CloverPit - And You Will Know Us By the Trail of Debt

I steer away from real-life games of chance because I have a flaw embedded into my genetic code. On my father’s side, the gambling bug — before I was born, he lost a small fortune to the Venice casinos. On my mother’s side, too — my nonna would spend every weekday evening at the Italian Social Club, playing Texas Hold ‘Em and Blackjack. It was only when Alzheimer’s ravaged her mind that she stopped betting.

I discovered I had a propensity for gambling when I went to Saratoga to bet on horse races, the moment I turned my last five dollars into a hundred. The rush I felt soared through my body and I felt like I was high. But before that, there was the devastation of shrinking funds when I put my money on losing horses. The comedown after one bad run. And I noticed the deviousness of the whole affair: the beautiful mares whipped by short men; the regulars guzzling beer, smoking their cigars, never missing a single race. I remember the blood. A horse had broken a leg and it twisted with gore and sinew.

I knew then that this was a slippery slope, that I had the same vice as my father and grandmother, and I could easily spend every waking moment gambling away the brief light of my life at the baccarat tables and the roulette wheel. I feel it when I snake through the halls of my local gas station, replete with slot machines, and I feel an incessant need to give one a whirl. I notice the dead-eyed stares of men just spinning the wheel, hoping for a large payout, and the feeling passes.

CloverPit feels like dipping into a bad habit after years of resisting the urge. I’ve relapsed before, always through the innocuous form of chance-based roguelike videogames. Thank God I’m not dealing with real money when playing Balatro because I would be destitute, even if the gambler in me is convinced I would be a millionaire. If the small gloomy cell in which you are trapped in for the entirety of CloverPit were representative of real life, I would already be a splattered corpse at the bottom of a vacuous pit.

A mysterious voice instructs me to go gambling, so the addict in me obliges.

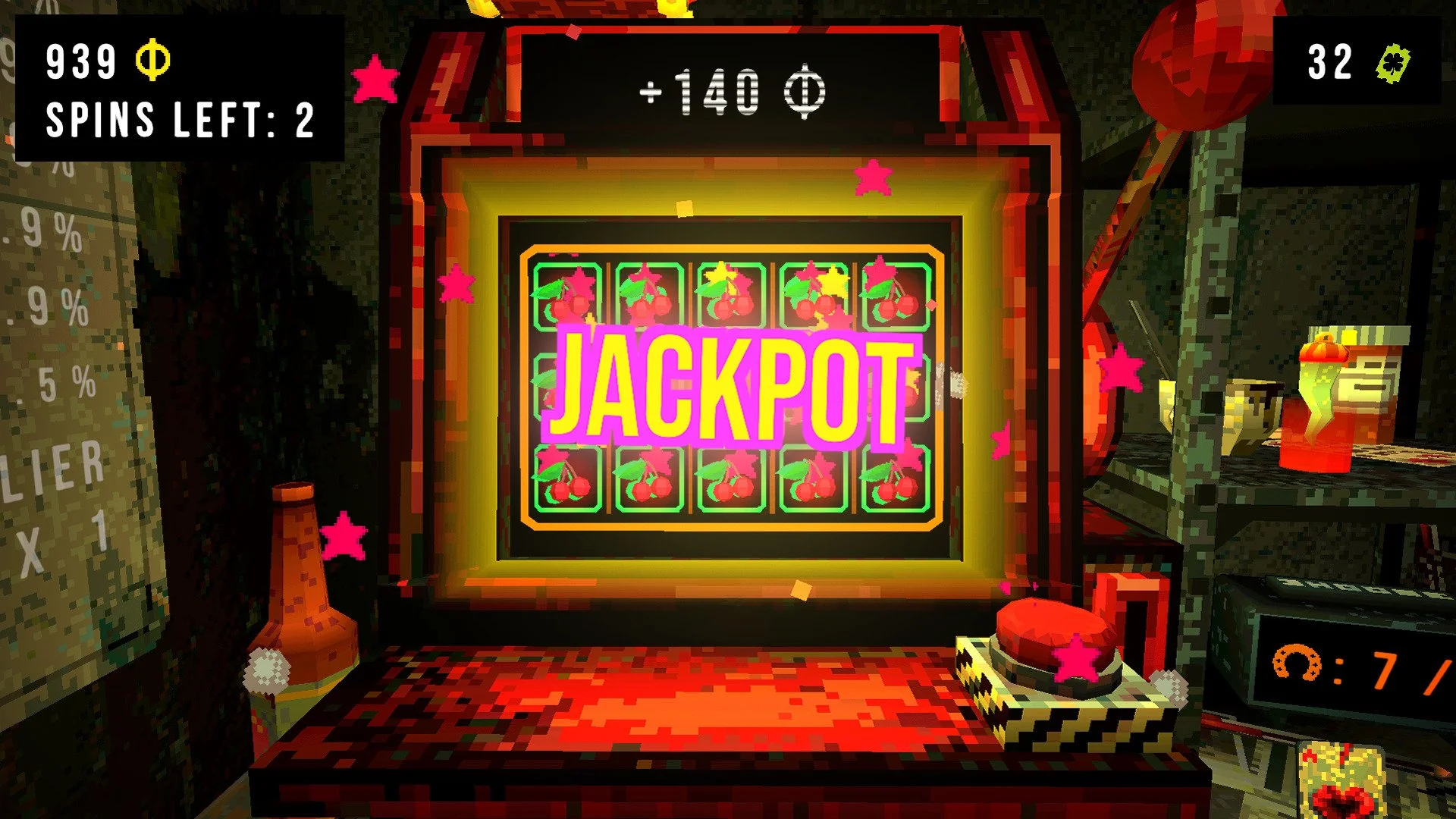

I insert the coins into the slot and crank the handle so hard it releases sparks. The machine chirps with life and the symbols spin with reckless abandon. Three bells line up in a horizontal line so a paltry sum of coins gets added to my total. I spin again: the symbols arrange randomly, without a discernible pattern, so I get nothing and feel like punching a wall. One more time and shiny diamonds occupy every single slot. Jackpot. Stars fly as my score gets counted, beeps and boops rise in a crescendo and they transform into a victorious symphony. The machine exhausts smoke, as if my last spin almost placed it out of commission.

I collect my coins at the end of my spins — the number of which is determined by how many coins I initially place into the hellish slot machine — and I step back to notice that a cabinet stuffed with entrails lies below the colourful screen.

The general cheeriness of the slot machine is juxtaposed with the rust-covered, blood-laden, cramped room that I find myself in. I look below and realise the floor opens like a trapdoor into a bottomless void. An ATM buzzes to the side, informing me I need to deposit 25 coins in three (now two) rounds. It is not just a debt-counter — it gives me a certain amount of coins as interest after each round, based on the total amount of coins I’ve deposited up to that point. Next to it, a small printer spits out green tickets adorned with clovers, which I use to buy precious charms.

Charms are your bread and butter — they are the mechanical juice of the game, because the slot machine, as you’d expect, can only be overcome with luck. The charms infuse it with magic, and turn the scales of chance in your favour — they can make certain symbols appear more often, add multipliers to patterns, and make certain patterns or symbols repeat when counted. Some even add a few points into a vague stat the game outright calls ‘“luck”, which, while badly explained, does net you better patterns, ergo, higher coin outputs.

Three rounds to make a deadline. Finish it early and you are showered with extra coins and tickets. A red phone rings after inserting the right amount of coins into the bank machine; pick it up for run-permanent perks. The charms can be disposed of if you find better ones. When destroyed, they spray pixelated blood. Maybe they’re all going into that gore-filled space beneath the slots.

After each deadline, the stakes increase — the slot machine requires more coins per spin, my debt rises exponentially, and re-rolls for the charms shop will cost me dearly. If I make it through enough rounds, then I receive a boon: a sacred key. Four keys unlock the drawers below the charms shop, which can be used to store the charms. Be warned: they rot into corpse parts when you lose a run. Nothing is saved when you fall down the pit. One key unlocks the gate of my prison. I am ashamed to say that, after dozens of hours and sleepless nights cranking away at the slots, I remain trapped and do not know what lies outside of my cell.

I keep failing, and dying, and the cycles of debt and addiction repeat.

Can’t make the next deadline…I crank the handle 7 times in a row and the machine doesn’t concoct any valuable patterns…that disembodied voice ridicules me like a financial dominatrix. The trapdoor below opens. Splat. Back to the start I go.

I despise “addictive” as a game descriptor because it is a shallow way of describing mechanical engagement, but I had an overwhelming compulsion to play CloverPit that took a few weeks to kick, when, similarly to when I saw the horse races, a more nefarious feeling crept into my mind.

I’m not talking about the dour setting or the fact that the Devil quite possibly lives inside the machine, or how those facets contrast with the cartoonish charm of chunky, dithering graphics, but more how CloverPit sinks its teeth into you in the same way a slot machine does.

Funny enough, given that the game contains a deep, dark, death-pit, I found the experience rather surface-deep — adorned with chirpy sounds and a tongue-in-cheek visual style that produces dopamine in some hidden part of my primate brain. It rewards a propensity for repetitive behavior with basic prizes, nothing more profound than that. The bloodiness is superficial. The mystery of the doors is not particularly unnerving, and my desire to see what lies behind them is merely a rote reaction borne of curiosity.

It seems like the game wants to make a statement about gambling, and wants to infuse it with dread and horror and mystery, but forgets that you need to rely on more than just set dressing.

The charms are funky — it was always joyous to unlock some new, useful one to harness its power — but, because the actual slot-portion of the game is so barebones, victory always feels like it is at the hands of the charms shop, which makes them more frustrating than endearing.

Dependence on lucky pulls is a staple of the roguelike genre, but CloverPit wavers in comparison to its brethren because it relies too much on chance. Say what you will about games like Balatro, or Inscryption, or Slay the Spire, but they all have some element of strategy involved in the affair other than just plain luck, and I oftentimes feel like I could jerry-rig a successful run out of bad cards or Jokers. CloverPit’s difficulty curve rises so steeply, from needing hundreds of coins one round to thousands the next, that if I didn’t get my known-to-be-good charms or have the funds for the necessary re-rolls to acquire said charms, then the run is basically a wash.

CloverPit is that special type of “one more run before bed” game that leaves you red-eyed and staring at the sunrise many hours later. How many times did I tell myself “one more run”, which then turned into twenty more?

There’s enough roguelike meat on CloverPit’s bones for genre fans to feast on. It still delivers the unique experience the genre promises — the synergy of perks and charms that grant the player the best feeling of all: the power to break a game entirely.

When I am winning I am loving it and I’m high again, when I am losing I feel my chest sinking and I am devastated when all my progress is lost. I love this friction, too — CloverPit kept reeling me back in over and over after I vowed “never again”, but I feel as if it is a toy that grips you for a few weeks, that you eventually put down for something more engrossing and holistic.

![[PATREON UNLOCK] Update Patch - September 2025](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5caf2dea93a63238c9069ba4/1760204153877-N6P1FMLC9HYDMZSTEWK5/MixCollage-11-Oct-2025-06-35-PM-5978.jpg)