Review | Mashina - A Handmade Gift

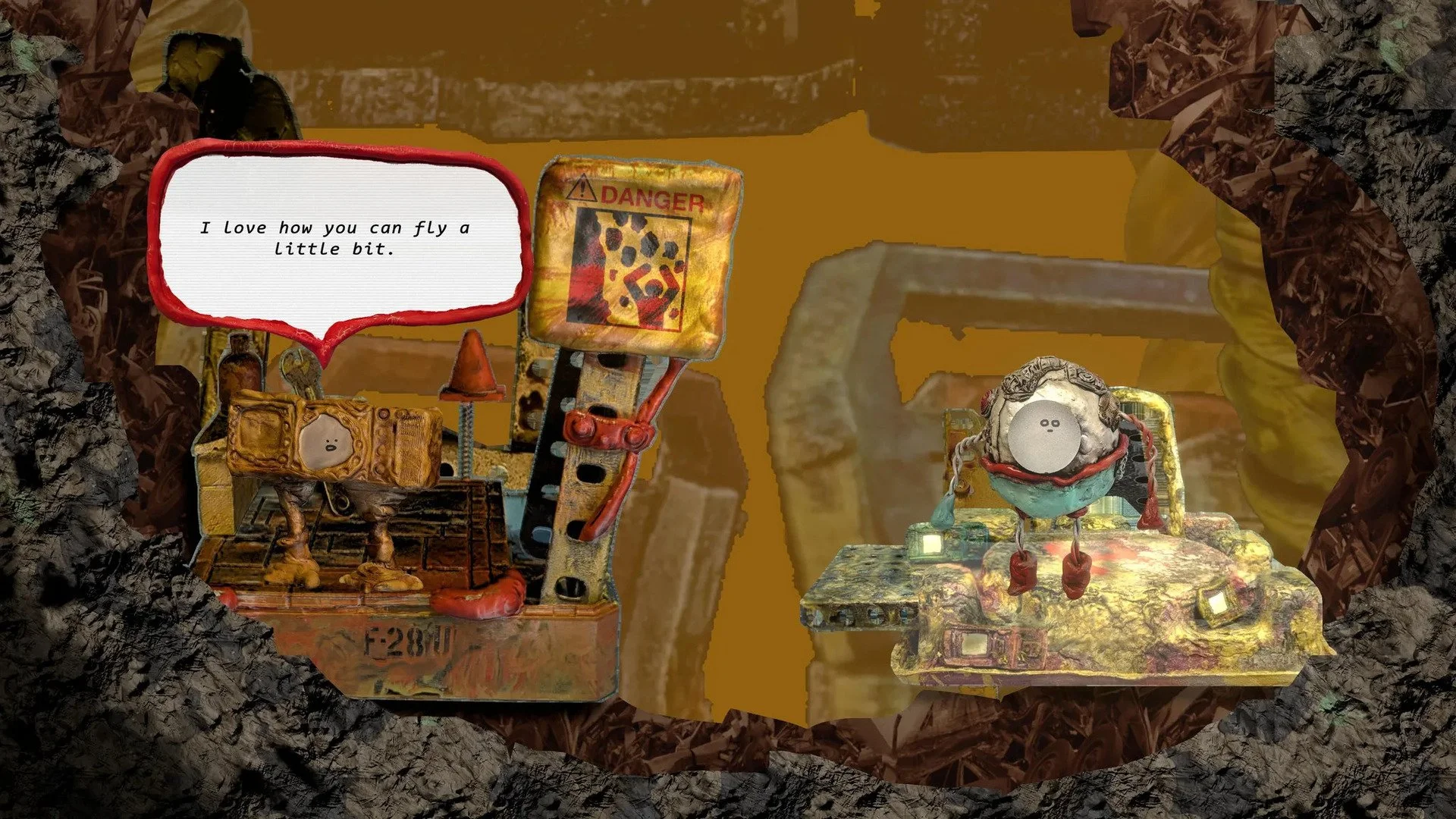

I brought new life into the world. From the depths, I recovered a mechanical cocoon and its appendages. I attached its limbs and the shell lit up, sparked by wondrous electricity. I don’t know who wouldn’t be moved to joy by seeing a mechanical baby sputter to consciousness, and witness her utter her first words with all the exaltation of a gleeful toddler: “Baby Mashina!”

Mashina is a charming game and has enough personality for me to recommend it on principle. I’m not here to state its handmade models and commitment to stop-motion are somehow unique — plenty of games have used such techniques in the past, though it remains rare in the medium — but its use of paradoxical combination of grotesquerie combined with a palpable joie-de-vivre, made me hold a smile throughout the entire short experience.

Shame about the gameplay, which is not at all bad, just somewhat passable — subdued and pressure-free. Mashina manages to escape the labour simulator trappings of similar games of its ilk not through gameplay innovation or engaging mechanics, but through atmosphere and artistic direction alone.

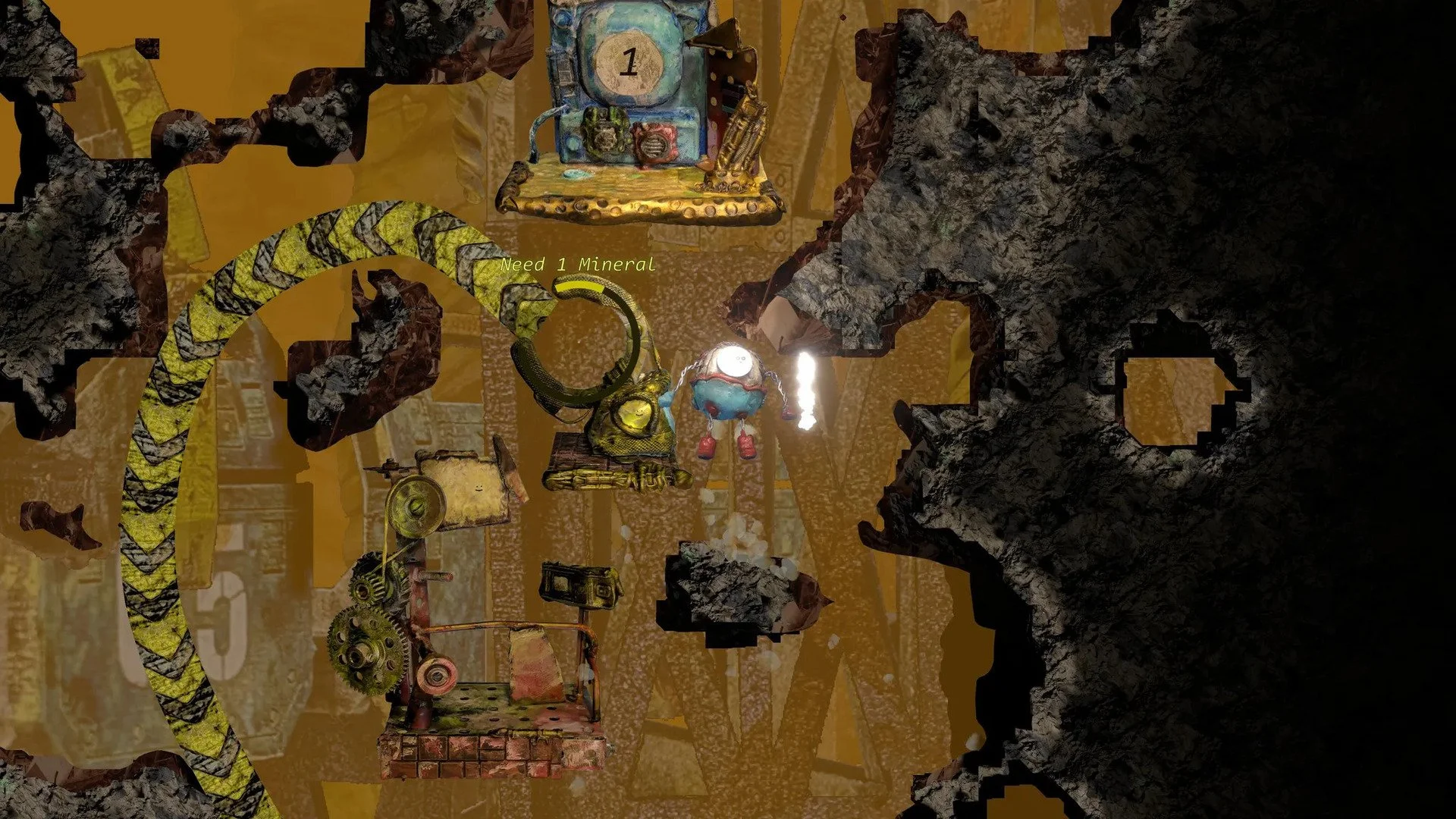

In the game, you play as Mashina, a helpful mining robot in a world of contrasting colours and mixed-media architecture. You split your time between the overworld, where you chat with quest-givers to receive objectives or turn in missions for rewards, and the underground area, which is where the bulk of your time will be spent, mining away the guck to recover shiny minerals, unearthing some kitschy decorations, building some shoddy-looking mechanical contraptions, and making some friends along the way.

Mashina’s most impressive achievement is the clarity of its visual language amongst the eccentricities of its art style. I was afraid all the handmade models would clash and collide when it came to the gameplay, and that the developer’s commitment to importing real-life materials into a pixelated world would stunt clear communication between the game and the player.

This is not the case at all: both the objects you can stick in your Tetris-style inventory as well as the machines (critters and objects both) that you interact with in the world are clearly demarcated with a subtlety that still allows them to blend in with the environment in aesthetic harmony. Minerals gleam in the vast caves and tunnels you excavate — they sparkle with a glittery synth riff that engages your auditory senses.

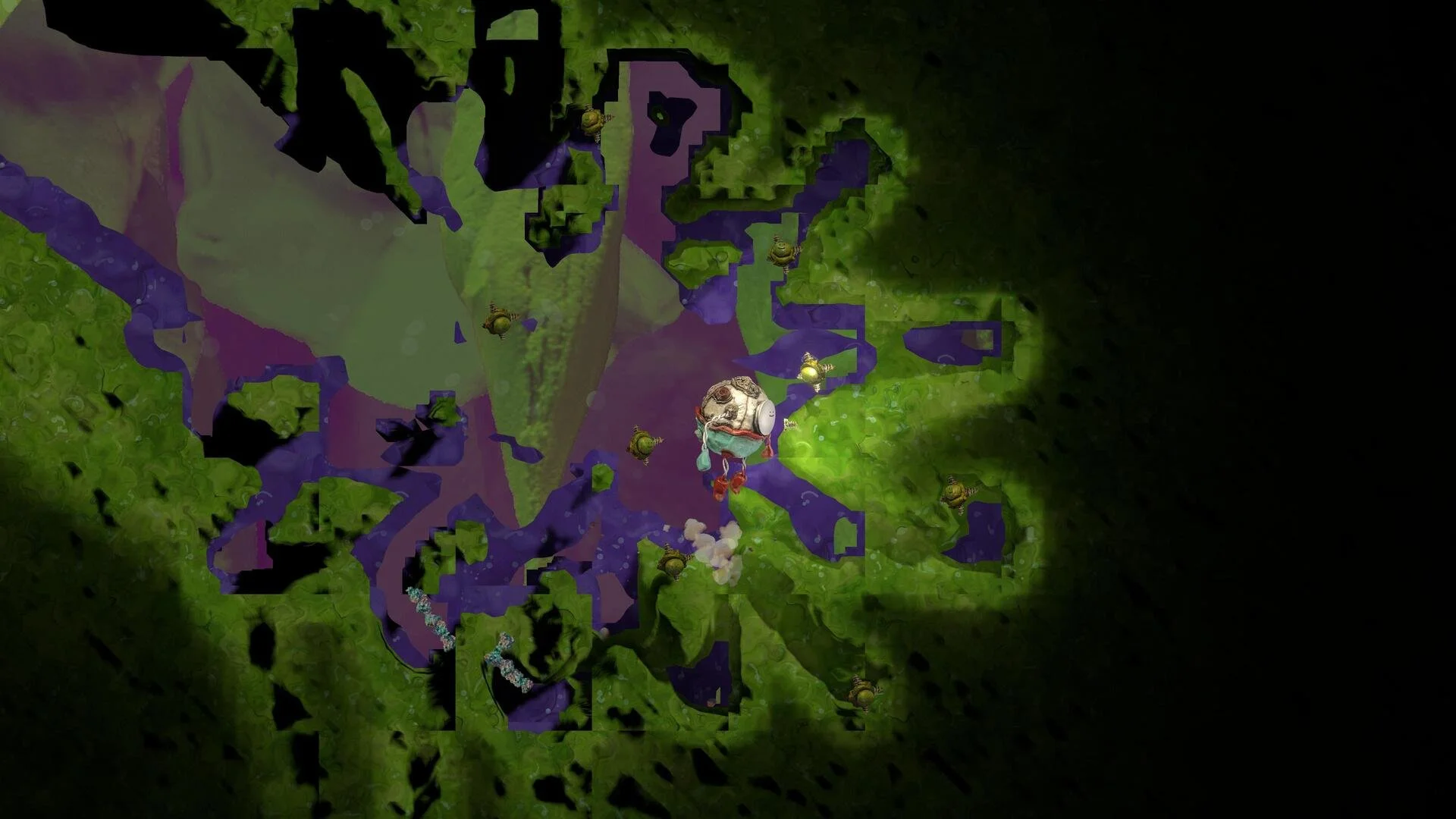

Above ground, the world is covered in a sickly-green ooze. Remote cardboard islands scatter the toxic ocean, from which structures of crumpled paper and clay rise, reaching for the vomit-colored sky.

You might imagine the inhabitants of this world to be some miserable geezers, but all you’ll find here are happy, friendly robots. Mashina’s mechanical friends are adorable, voice acted and animated with all the charm of a surreal children’s show. At their behest, the eponymous robot delves underground and recovers some goodies or minerals, and they respond with such gleeful gratitude upon delivery that they painted smiles on my face throughout the game’s short duration, not dissimilar to the characters’ own drawn-on visages.

Your efforts do not go unrewarded — in return they will grant you experience points, or upgrade your drill, or they’ll build a bridge to cross to a new island or even a spaceship to see the stars. And is that not enough? To sweat and toil not for extraction of resources or acquisition of material wealth, not to ever-expand an automaton factory like a cancerous cell, but simply because your community thinks it would be “really cool” to venture into the mines with some new gizmo or goal? Regardless of experience points or upgrades or fancy new tools, you do these favours not because there’s much rhyme or reason, but because your friends are asking you to. What refreshing, childish bliss.

It’s a double-edged sword: the subdued gameplay experience opens up a lot of room for relaxation, allowing for the game’s personality and art style to shine through, but as someone who seeks friction in gaming, the various ventures into the mine ended up turning dull and monotonous.

Collecting resources is pressure-free. There are no time limits, nor many different materials to keep track of. You don’t need to constantly extract certain resources from the Good Earth, nor are you required to design machines of industrial automation, despite the world’s many conveyor belts and mineral-processing machines. There’s a hypnotic effect to seeing earth and stone slowly dissipate under the power of your tiny motorised drill. But, outside of heartwarming visual ephemera, the actual gameplay didn’t inspire me with the same feeling of gusto.

There is not much of a narrative or tension to be found in the game. There are no fail states; you just head down with your trusty drill into the mines, take your time completing favours for the robots topside, and chill out. You spend your time basking in the surreal, psychedelically-ebbing dirt and the eclectic soundtrack — a mashup of vintage synth drones and guitar strums that all coalesce to curate an inscrutable vibe.

This game is built for the explicit purpose of relaxing, which is not (always) why I play games. I want to be challenged, and I am not stating this solely as a matter of gameplay difficulty, but also about what happens in the mind — being prompted to think about difficult themes, unpacking interesting narratives, and connecting with the emergent experiences that might bloom from deep, mechanical engagement with virtual worlds.

It would be easy to decry Mashina as a “style over substance” game, but I will always argue that style is substance — an engaging visual experience is enough, and while Mashina doesn’t make any big strides with either its story, themes, or gameplay, it left me with a warmth I still feel now.

Mashina is a prime example of how much charm and personality can save a videogame. It is one of the few games I’ve played that actually lives up to the “cozy” and “wholesome” descriptors, an achievement given the odd character designs, beings that seem to be slapped together with knickknacks and wiring, and the weirdness of its environments, which overflow with different textures rendered in muted yellows and browns.

While not as chaotic or outright weird as Talha and Jack Co.’s previous release, Judero, Mashina ends up being an endearing and life-affirming work of art that stresses the importance of friendship and reciprocity as communal pillars. The game is an incredible decompression tool — it is impossible to meet Mashina and her friends and come out of the experience with an unmelted heart. It is a refreshing work of handmade whimsy and passion, but it is as malleable as the clay figures it is adorned with: it is not a game that offers much resistance, and this subdues the effectiveness of the aesthetic cacophony the developers have cultivated.