I Beat OFF And All I Got Was Climate Anxiety

I have always imagined the end of the world as the heat death that ceases everything. The end of the world in OFF, is encompassed by eternally illuminated stillness, a purification, yet what kind of world does it replace? One where bureaucrats donned buttoned up white shirts and black ties, living in constant fear of attack from shades and spectres. You could see it in their eyes, their fearful stares of heightened awareness.

This world was oppressive enough without the threat of ghost attacks. ‘Something’ happened, a cataclysmic event that has left the world unable to progress, stuck in an industrial post-apocalypse where bald clones of office workers still go about their labour routines despite deadly working conditions.

They extract various resources from the ground: smoke, metal, meat, plastic, and a secret, valuable fifth element. The workers process them; plastic turns to liquid which segregates the different Zones and islands from each. Most of the elements are real-world contaminants.

OFF’s cult status is legendary, its themes multiform. It is rife with complexity, symbolism and depth, yet vast enough to allow for oodles of player interpretation. It’s as much a game about video games as it is a game about illness and the dichotomy between utopia and dystopia.

I would argue, however, that the most interesting theme in OFF relates to climate change, and the palpable anxiety it leaves, the spectre of climate change that still haunts us a decade ahead of its original release.

In the game, it’s metal that is harvested from pastured cows. Meat, for its part, comes from an unknown source and is bottled, then distributed around the various Zones that form the world of OFF. In real life, the steel industry contributes about 7% of global greenhouse gas emissions, and the livestock industry even more, accounting for around 14.5% of emissions. Without plastic there would be no Zones: “The world would have no boundaries. People would walk and walk without ever stopping.” Without plastic there would not be a new man-made island, the Great Pacific Garbage Patch. Smoke strangles us all, but it’s a life force in the world of OFF: “Without smoke, no one would be able to breathe.” Yet, I often have to wear a mask outside, when my city is plagued with smog from wildfires.

Sugar is OFF’s secret element: “The most important element... Because without sugar, people could no longer bear reality, and they would go mad.” It is not explicitly a polluting element, but something much more nefarious — a method of control, a vice to keep the population docile and lenient. It is made by burning the bodies of deceased labourers. An echo of Charlton Heston’s scream in Soylent Green, sugar is people, and workers of Zone 3 devour their fallen comrades, none the wiser, their only respite after an arduous shift.

These elements act as affinities you imbue into the baseball bat wielded by the player character, the weapon of purity. Named for his function, the Batter runs with dementia and courage, striking at fiends with metal and smoke. The Batter will gladly use the elements in order to rid the world of them. He is a promise that these elements will cease to be, but he, in turn, will snuff the life out of the world and its labourers.

“I am Alpha and Omega, the First and the Last, the Beginning and the End”, so spoke the Lord. The Batter is joined in battle by halos, the start and end of all things, Alpha, Omega, and an additional middle space, Epsilon. Zealotry is inherent to the Batter’s actions — everything that doesn’t fit his vision of the world must be purged, and only that which is holy and sacred must remain.

Sin is often equated to dirtiness. “Cleanliness is next to godliness.” I wash myself of my sins, all the pollution of my soul, and I am free and redeemed by the Lord. But yet, I remain a sinner. In the Batter’s utopia I too would disappear — the absence of sin is the absence of all life. A baptism for the Batter means the end of the world, and the death of all the zany, wacky caricatures that populate it. Zachariah and his store, the Judge’s toothy grin, all burned away by blinding light.

Even the word “purification” (present in every post-battle splashscreen, which reads “Adversaries purified”) evokes climate anxiety, and an urgency to rid ourselves of impurity. It speaks to a world undiluted by pollution, for the world the Batter wants is free of smoke, and liquid plastic, and metal-bovines. It is an empty place, but there is no pollution. There’s also no human or animal life to produce said waste.

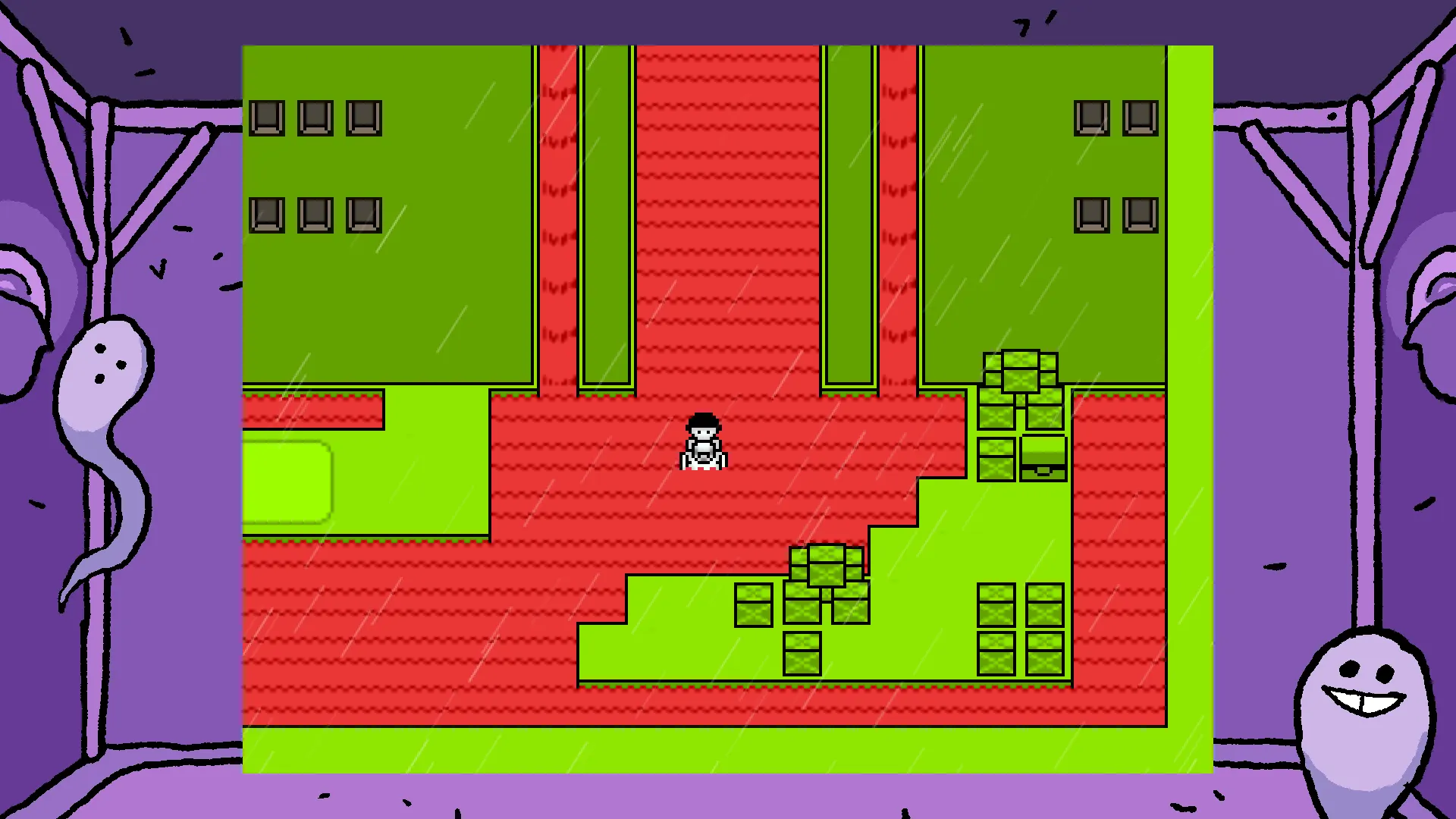

The things that kill us in the real world breathe life into the Zones of OFF. Not just life, but colour: despite its contamination, the world is not grey and sullen, but vibrant and bright. It is only when a Zone is purified that an oppressive white covers all, and its inhabitants disappear, replaced by grotesque boxer-babies who attack the Batter and his crew. Everything is purified, but violence remains. Violence always remains.

While in many games the avatar is a placeholder for the player, OFF clearly delineates and separates the two. In the end, it allows for the player to be opposed to the Batter’s plans of purification. While you must control him through to the game’s final moments, you can oppose the Batter’s dogma.

After fighting many battles and beheading a Queen, you re-encounter the Judge — the Cheshire Cat with a permanent smirk you met at the beginning of the game — at the final pedestal, standing in front of the lightswitch of the world, which is currently flipped to On. The Judge then asks you, the player, to help him directly, expressing disgust for your aid of the Batter’s crusade.

If you join the Judge, you fight and defeat the Batter, and the cat walks through the now empty Zones in sadness. No more dirty pools clog the arteries of this place. The world of OFF has already died and it is too late to bring it back. All you could hope for was revenge against the Batter.

However, if you join the Batter, you massacre the Judge and you flip the switch to Off, and the screen fades to black. Whether in darkness or an even more blinding light, who can say?

I reject the reactionary idea that humans are a blight on the world and must be removed entirely in order to end the apocalyptic effects of climate change. I do not believe the responsibility to end climate change is a purely individual one, as if every packet of plastic we dispose of is equal to industrial or military pollution. In the same way industry dirties up the world of OFF, so do corporations overwhelmingly produce the majority of greenhouse gases, not individuals.

Which isn’t to say individuals shouldn’t focus on reducing their waste: what I took away from OFF, other than the panic of climate anxiety, was the reaffirmation that I have agency, that despite all my worries over the end of the world, there are many like me who believe in a better-nurtured environment, safeguarded from unchecked pollution. That, as a global society, I believe we are able to reverse the effects of climate change, even if not completely, at the very least enough to save us from premature extinction. It also reminded me that I can oppose those who seek to dart us ever-closer to the end of human civilization for their own enrichment (looking at you, CEOs of various oil companies), but also counter the idea that humanity itself is the problem.

I beat OFF and I got climate anxiety, but it reaffirmed I can still fight.

OFF was played on PC with a code provided by the publisher.